Okay, let’s start again. One professor with a TED Prize wish tells a hall full of English teachers that sometimes kids learn best with no teachers around. Teachers react differently. Teachers have discussions. Teachers write blog posts, ask questions (the professor answers some of them).

I want to move beyond teachers today. There’s plenty in this conversation for a language learner. And if the whole idea of teacher-less learning is discussed by educators, it should at least be on the radar of some future polyglots.

Here’s a hint before we begin, though: many of us have been doing this for ages.

0. A man and a computer walk into a slum…

If you’re new to the whole story, I suggest you watch Sugata Mitra’s TED talk before you read on. This will be the briefest of introductions to what follows, but don’t worry – we’re moving on quickly. There are some other videos available in the links above, too.

1. Learning without teaching: a brand new idea (that wasn’t)

The idea that children can learn things simply by interacting with a computer and one another – the idea that learning, even learning vocabulary and pronunciation of English, can happen without the teacher’s intervention – this is what stirred up so many teachers who found themselves at the receiving end of Sugata Mitra’s manifesto.

But if you look closer at the thinking behind these experiments, you’ll find that they aren’t really revoutionary. I don’t want to go into much detail here, as this would be of more interest to language teachers than learners – but I will point out three things here:

– Sugata Mitra’s “Minimally Invasive Education” is similar in many aspects to guided discovery learning – a model of learning used well before any hole-in-the-wall experiments.

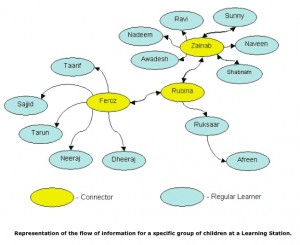

– It’s not true that there are no teachers in the experiments described: the figure below (click for source) shows that some children take over the role of “connectors” quickly, helping others out:

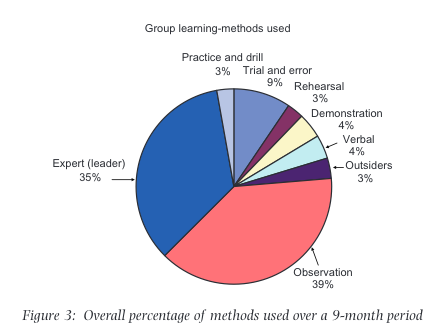

– Finally, it follows that even within the environments that lack “real” teachers, someone will take over the role of the expert, and somebody else will watch and learn (as seen in the figure below, click for source).

Language teachers will read into those papers what they will. Foreign language students have a different thing on their mind, probably: how does this help me?

2. How Sugata Mitra’s Experiments Will Help You Learn That Language

It’s ironic that for many enthusiastic language learners, the computer-led scenario is actually coming true already. A lot of language instruction is moving online – and there are many good things to be said about that. But it’s easy to stop there, and rest satisfied that we’re actually making progress just by opening our language learning software every few days and going through a few exercises.

What language learners should focus on in this scenario is not just the computer in the wall, but the group of folks around it – not only what’s happening on the screen, but mainly what’s going on alongside the street that hosts it.

This is where interesting things happen. This is where a neighbourhood kid turns out to be your expert for half and hour. And this is how you watch, imitate, fail – and learn.

I’m simplifying to make a point, but it’s a point I’m ready to defend: you don’t always need a teacher. You don’t always need software. But if you’re learning a language, you will always need communication at some point. And this is where Sugata Mitra’s experiments can be a good starting point – if you’re willing to hack into it and have it your way.

3. Hole-in-the-wall learning – a DIY checklist

– Work with teachers who ask good questions and demand more.

– Find out ways to “go it alone” with the language you’re learning (i.e. without teachers)

– Watch people who do things in your foreign language. Sit at a cafe table, go to a meeting where you’re not expected to speak, stroll around. Do this mindfully, don’t give yourself any slack: the tone of voice, the facial expressions, the body language – this all becomes your syllabus.

– Work with material which challenges you. Going over basic verb forms may feel good and safe, but won’t help you grow in the long run.

– Find your own “connectors.” Super-nice old lady at the Greek pastry shop? Brush up your “kalimera” and see where that takes you. A colleague married a Spanish guy? Go out for coffee with him once in a while. That classmate of yours – making lots of friends and being really extroverted about his language study? Go to a party with him, even if it feels super-awkward. Look for people who can teach you things.

– Enjoy admiration. Learning someone else’s language – and finding the courage to use it – doesn’t make you look strange. It’s a brave, appreciated gesture in 9 cases out of 10. A bit like Sugata Mitra’s “grannies” who admire, ask questions and make learners discover more – native speakers of the language you’re learning will quite possibly cheer you on and make you want to use the language again.

– Enjoy every bit of learning technology you can find… between your computer, your mobile device and your library, the choice is bigger than you think.

– …but count on a good teacher to intervene, guide and fix things on the way – and get your language skills to where you want them to be – in good time and form.

4. So what did you make of that, then?

These are interesting times for learning and teaching – but so far, it’s the teachers who make all the (cheerful and angry) noises in the debate. Let’s hear from the language learners! Do you think Sugata Mitra’s approach has anything to offer to you in your study?

Wiktor (Vic) Kostrzewski (MA, DELTA) is an author, translator, editor and project manage based in London. When he works, he thinks about languages, education, books, EdTech and teachers. When he doesn’t work, he probably trains for his next triathlon or drinks his next coffee.

BRAVE Learning (formerly known as 16 Kinds) is a lifelong learning and productivity blog. If you enjoy these posts, please check out one of my books and courses.

My recent publications, and my archive, is now all available on my new project: PUNK LEARNING. Hope to see you there!