The Welsh word “ysgol” means two things: “school,” but also “ladder.” I found this out on a trip recently and was surprised at how accurate this is.

There’s a lot to be said about the way schools are organised – plenty of good things and some horrible things can be witnessed there as a result. When it comes to language schools, here’s what it boils down to. Prepare for an unceremonious, frank inside story of a language school manager – and how you can beat the system if you really want to.

The Ladder Benefits

Just about every language school in the world has levels. This is one thing that nobody dares to question, and everybody assumes to work with. Levels are the bread and butter of language learning.

You finished one level, on to another one. You’re having problems, tough – repeat this level. You’re brilliant and gifted – great! Skip a level.

Levels are how language schools deal with their teachers, learners, courses, course materials, prices, requirements, publicity – almost everything revolves around this idea.

And it’s great, effective and simple. I have lots of genuinely awesome things to say about the idea of having levels in a language school. I’m going to give you a quick list – only limiting myself to the benefits that relate to learners:

– It gives a sense of progression. If you’ve finished one level and progressed to the next one, you feel that you’ve achieved something. So it is with video games and foreign languages 🙂

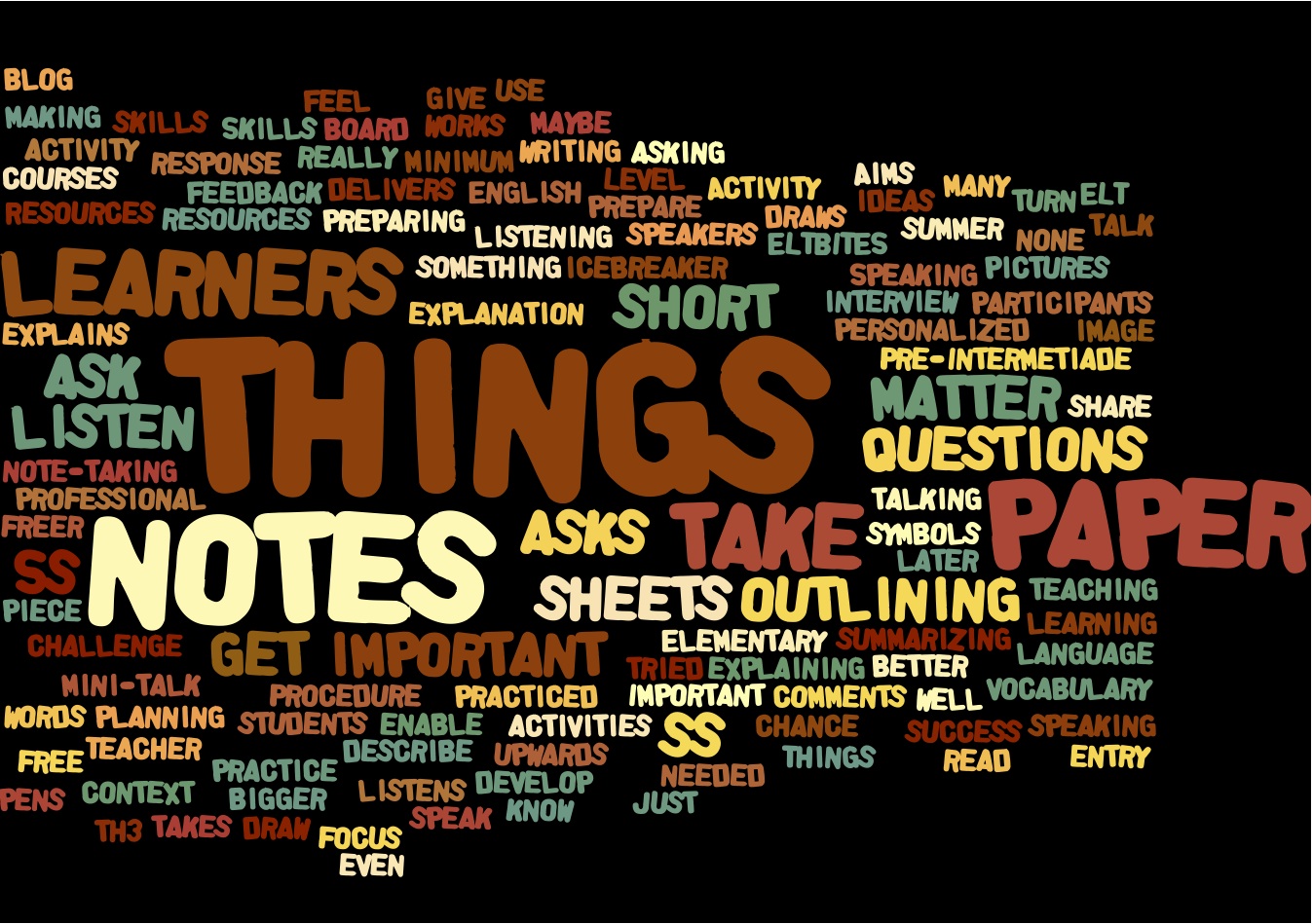

– It’s pretty well thought-out. Predictably enough, the folks at various European commissions have liked the idea of proficiency levels for language learners. The result is a framework which outlines what learners should be able to do as a result of completing each level. I like the idea of measuring proficiency in terms of what you can do with your language – who cares how many words you remember, if you’re unable to write a simple email?

– It makes learning manageable. Low levels learn basic things. High levels learn advanced stuff. This is how you avoid stressed-out, unhappy learners. This is how learners can actually make progress.

– It introduces order into some pretty shambolic circumstances. When you sign up for a language course, you’re in for role-plays, tests, listenings, dialogues, games, homework and who knows what else. It’s pretty intense, even in small-sized classes. So it feels good to know that “this is my level, and the next one is that.”

Cutting up the river: the absurd of levels

The disadvantages of levels in language learning may not be so numerous – and they’re definitely more abstract. But I feel that it’s just as important to mention them – as a person responsible for managing how people teach and learn, I have frequently faced their absurd nature. So I’m venting a bit, but also giving you a fair warning. Here goes:

– Levels are arbitrary, abstract structures. Changing the label on you classroom door from “elementary” to “intermediate” does absolutely nothing to your language. You still know what you know, you still learn what you want to learn.

– They tend to be too restrictive. “We won’t learn the passive voice until intermediate.” “Don’t waste time on that graded reader, the level’s too low for you!” Many schools, teachers and managers will refuse to look beyond the level. You’re here, the thinking goes, so you will learn the things your level allows you. No more, no less.

– They introduce competition into a non-competitive field. If a language school tells you that it will allow you to cover twice as many levels in five years – they’re doing two bad things. Firstly, the school makes you believe that going through levels fast is a good thing. Secondly, it makes the other, more thorough schools look bad in comparison. If your goal is to beat the world record in memorising vocabulary, be my guest – but if you want to learn a language really well, then my first advice would be to take your time. Yours, not someone else’s.

Level Up: how to beat the level-crazed system

The most important piece of advice for learners in a level-based language school?

Hold the school to its word. A level is something that should work for you as well.

[checklist]

- Find out how long it takes to complete each level.

- Learn about the whole level range the school can offer – and if anything is missing (what happens at the top?)

- Find out if there are any exams available after each level.

- Request a framework of key skills and competences for each level.

- Ask for a non-level class, offering authentic language practice (works mainly for advanced classes – but always worth a try.)

- Demand that all tests be marked in references to the syllabus and skills framework for the level.

[/checklist]

What are your thoughts on levels in language learning? Don’t be afraid to comment!

Wiktor (Vic) Kostrzewski (MA, DELTA) is an author, translator, editor and project manage based in London. When he works, he thinks about languages, education, books, EdTech and teachers. When he doesn’t work, he probably trains for his next triathlon or drinks his next coffee.

BRAVE Learning (formerly known as 16 Kinds) is a lifelong learning and productivity blog. If you enjoy these posts, please check out one of my books and courses.

My recent publications, and my archive, is now all available on my new project: PUNK LEARNING. Hope to see you there!